Exploring the creativity and creative thinking conundrum

Research 1 Jul 2021 5 minute readUnderstanding creativity and creative thinking can be tricky, which makes assessing such skills even more challenging.

Researchers across the globe have defined creativity and creative thinking on a wide spectrum of beliefs. On one extreme is the belief that creativity originated in supernaturality or ambiguity. At the other extreme are scientific definitions of creativity as an input, process, or product:

- Input: thought process of an individual to generate creative work

- Process: a series of stages for generating new ideas

- Product: as a useable application

By all means, creativity is a complicated psychological phenomenon. Most of the approaches used to study creativity can be placed into six categories: mystical, pragmatic, psychodynamic, psychometric, cognitive, and social-personality. Table 1 provides the key terms and their pioneers.

Table 1: Different approaches to creativity based on ‘The Handbook of Creativity’ (Sternberg, 1999).

| Name of the approach | Key words | Pioneers |

| Mystical |

|

|

| Pragmatic |

|

|

| Psychodynamic |

|

|

| Psychometric |

|

|

| Cognitive |

|

|

| Social-personality |

|

|

The fact that there is no generally accepted definition of creativity has not undermined its importance as one of the essential components of 21st century skills. However, the lack of a generic definition has created difficulties for school teachers responsible for nurturing creativity in their classrooms.

In education, psychometric definitions of creativity can be of great help to teachers and, fortunately in these definitions, two common attributes – 'originality' and 'usefulness' – are consistent. For example, Sternberg and Lubart wrote in 2000 that creativity is the 'ability to produce unexpected original work that is useful and adaptive'.

The terms originality and usefulness provide a common understanding but do not take the pressure off teachers engaged in assessing them. The 'originality/original work' is subjective and non-measurable.

Some definitions of creativity are centred on divergent thinking. One of the prominent 1950s researchers, Guilford, used divergent thinking in the formal measurement of creativity. He defined divergent thinking as the ability to generate multiple solutions to an open-ended problem. Although, creative thinking and divergent thinking cannot be considered synonymous, both indicate the cognitive process of creative thinking which may lead to original ideas and solutions. Measurements of divergent thinking were prominent in assessing creativity in the latter half of the last century. For example, Urban and Jellen suggested testing creativity by asking participants to complete a drawing using some given figural fragments. Through the resultant figures, the divergent thinking component of creativity can be measured but again the 'usefulness' factor is not counted. Additionally, the judgement parameters did not eliminate subjective judgement of the resultant figure.

In 1961, Rhodes suggested that creativity can be assessed using personality features and dispositions of an individual and observable learning and thinking involved in a creative act, product, and the environment including social factors. Many researchers have focused on assessing creativity using one, or at the most two, of the four aspects suggested by Rhodes. For example, in the habits of mind model, the assessment focus was on individual dispositions, and on the social aspects of creativity. Others suggested that creativity can be measured by observing students' behaviour while performing tasks. Again, subjectivity and a high level of competency are required while interpreting such results.

To avoid such subjectivity, ACER's skill development framework supports teaching and assessing creative thinking and is focused on both the process and the end product. It considers creative thinking as made up of aspects that are observable and measurable with the help of techniques for standardised assessments that can be easily administered in a classroom.

ACER's definition of creative thinking:

'Creative thinking is the capacity to generate many different kinds of ideas, manipulate ideas in unusual ways and make unconventional connections in order to outline novel possibilities that have the potential to elegantly meet a given purpose.'

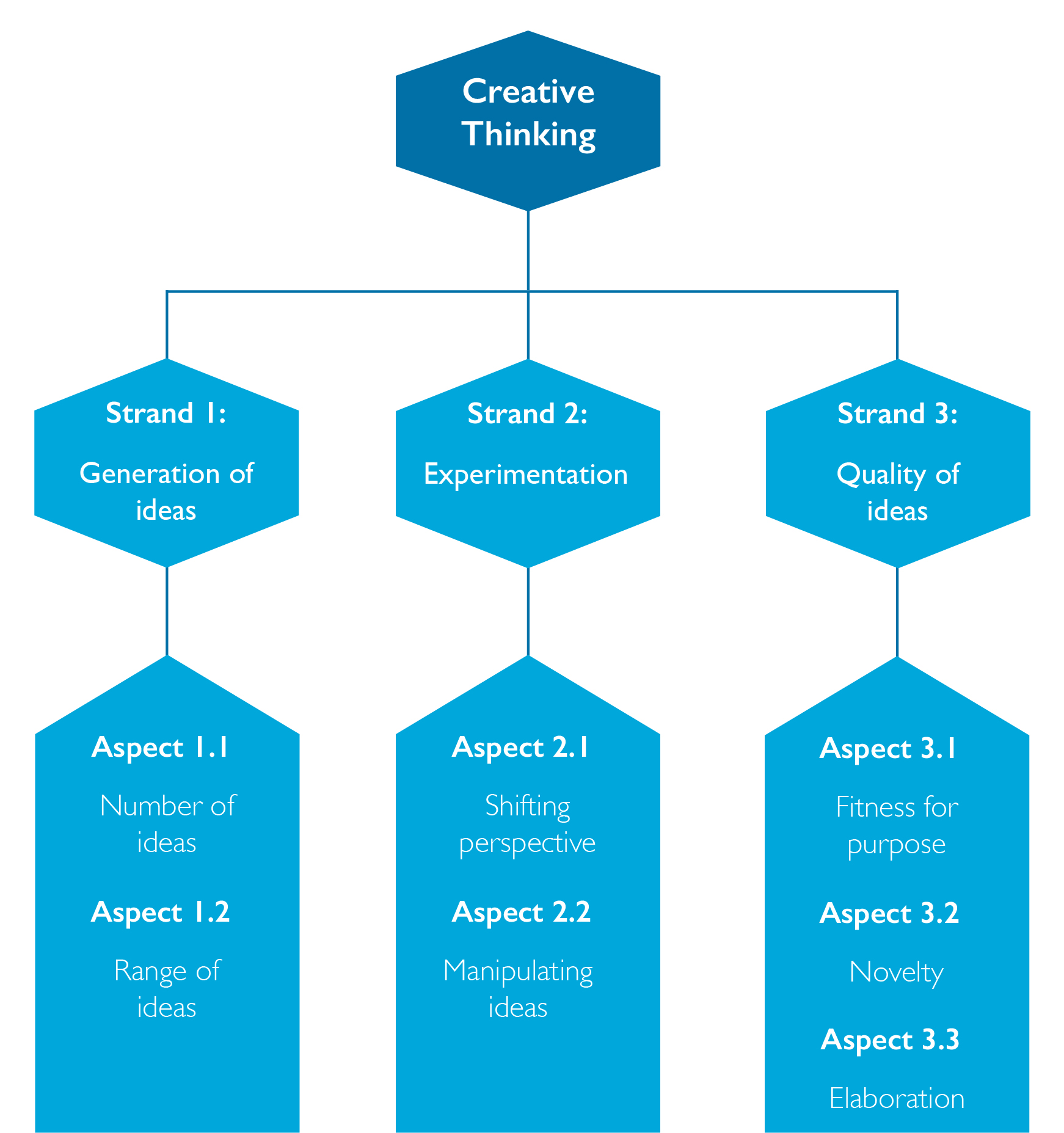

ACER's creative thinking construct is defined according to overarching strands, which are key sub-skills or concepts that support creative thinking, and, within those aspects, which define how the strands might be observed and assessed. ACER's creative thinking framework consists of three strands, including seven aspects in total, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: ACER’s creative thinking framework

This framework outlines the creative thinking which students undergo while solving a problem or undertaking a task. Each strand of creative thinking – the generation of ideas, experimentation, and the quality of ideas – is then elaborated upon to provide guidelines for teaching and assessing creative thinking in school settings.

This clear and practical definition of creative thinking with consideration of progressions can be of great help to teachers. The assessment of creative thinking in specific school subjects can provide a reliable indicator of mastery in those subjects.